I’m taking a much-needed break from writing my actual thesis and instead looking at the art produced for extreme metal music albums. In this way, I feel like I’m paying homage to my first love in academia: art history.

I recently came upon an interesting CFP on my blog feed from the University of Winchester. This upcoming summer, they are holding a conference on Death, Art, and Anatomy and put out a call for papers on any research having to do with the following topics:

- Death and art

- Anatomy and death

- Anatomy and art

- History of anatomy

- History of death

- Religion and anatomy

- Religion and death

- Medieval and early modern death beliefs and practices

It got me thinking, and I started to explore the idea of how some extreme metal album art could be an extension of the medieval concept of grotesque realism.

So I began reading and discovered previous research making this claim by author and Professor Karen Bettez Halnon. In her paper, Heavy Metal Carnival and Dis-alienation, she examines the use of grotesque realism in performance, lyrical construction, and the appearance of bands like Gwar, Slipknot, and Cradle of Filth. Although these bands are not all categorically extreme metal, it made me think about controversial extreme metal cover art that has been produced in the past few decades.

Referencing philosopher and critic Mikhail Bakhtin, Halnon defines grotesque realism in relation to her study as a form of “heavy metal carnival,” whereby the noise of commercialism is dismantled and transgressed by heavy metal’s ability to challenge societal norms of conduct, dress, taste, morality and civility (Halnon, 2006). What this encompasses is a fandom and culture that encourages the obscene and bizarre, disassociating it from general musical audiences that would favor more socially-accepted styles of popular music, visual art and fashion.

As an example, she cites the band Gwar, who spray their “slaves” (the audience) with red-colored water (symbolic of blood) and other bodily fluids, effectively enacting a spectacle of grotesque through fantastic and fictional displays of human dismemberment, torture and beheadings. On its most base level, this spectacle transgresses the limitations of real and fantasy for participating fans. Like Halnon believes, “the display signifies the creative life-death-rebirth-cycle”. (Halnon, 2006)

Within the paper, Halnon echos Bahktin’s own definition of grotesque realism as:

Within the paper, Halnon echos Bahktin’s own definition of grotesque realism as:

““Eating, drinking, defecation, and other elimination (sweating, blowing of the nose, sneezing), as well as copulation, pregnancy, dismemberment, swallowing up by another body—all these acts are performed on the confines of the body and the outer world, or on the confines of the old and new body. . . . The grotesque image displays not only the outward but also the inner features of the body: blood, bowels, heart and other organs. Its outward and inward features are often emerged into one.” ([1936] 1984: 317–18)

Does this not sound like extreme metal to you? Hanlon goes on in her paper to talk about inversion within the heavy metal carnival. What really caught my attention was the following:

“The carnival-grotesque is not only exposing the deep (hidden, vile, disgusting), interior aspects of anatomy but also what is spurned, spoiled, stained and hidden in the body politic. Inverting the ordinary devaluation, invisibility, or “symbolic annihilation” of those positioned at the bottom of (social) hierarchies (Larry Gross quoted in Gamson 1998:22)”

These two statements mark further evidence of the grotesque for lyrics constructed by extreme metal bands like Carcass, Cannibal Corpse, or Deicide. However controversial the works of these bands and bands like them can be construed, it made me curious to explore the imagery depicted on albums of this nature.

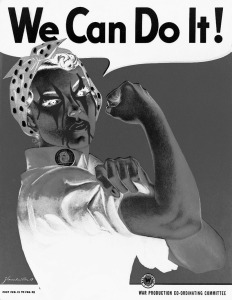

Furthermore, I wondered if the often violent and horrific covers of extreme metal albums were indeed an extension of both the medieval grotesque and heavy metal carnival, then what research, if any, was being conducted specific to the treatment of women, so often depicted in controversial images flagging the albums.

If I decide to write a paper for this conference, I think it will broadly speak to the use of grotesque imagery on extreme metal albums as a form of intentional aesthetic and then move more specifically to the depiction of women, particularly the thematic imagery of Death and Women on covers.

\m/ –Hail Metal– \m/